Visualising Heritage

The University has amassed the remains of more than 4,500 archaeological individuals from many different sites – the largest such collection in any UK academic archaeology department, ranging from the Neolithic to the 19th century.

Researchers are interested in human remains that show recognisable signs of disease. However, repeated handling can cause damage. Ancient remains are important in furthering understanding of how disease is manifest within the skeleton. Diseased archaeological bone can help modern medical research and training. In many parts of the globe chronic conditions that ultimately affect the skeleton continue to flourish, including osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, dental abscesses, and rickets caused by vitamin D deficiency in childhood.

Without access to bone elements, medical students and radiographers depend on textbooks, or radiography and related imaging techniques, to see the skeletal changes.

Digitised Diseases is a web resource that contains photo-realistic 3D models of bones, together with detailed descriptions, clinical synopses, radiographs and CT data. The resource holds more than 1,620 scanned specimens accompanied by some 1,425 descriptions. There are over 550 radiographs and several hundred CT scans.

It is a fully open-access web resource. It addresses training needs in biological anthropology, history of medicine and for clinicians concerned with chronic conditions, neglected diseases and re-emerging conditions. The resource has been accessed more than 3,437,887 times globally.

Heritage is about more than monuments. It is also about people: how they interacted with the buildings and how their sense of belonging has shaped them. The Curious Travellers project uses a resource that exists in abundance: the photographs of millions of tourists and locals worldwide.

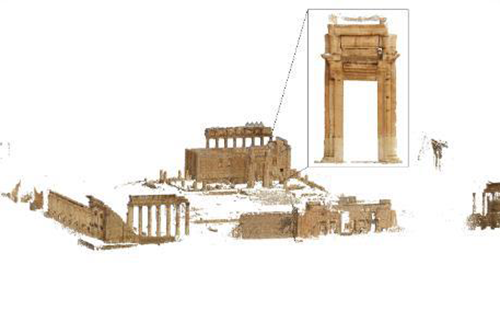

These images are augmented by data to create accurate 3D models of ancient monuments and sites. Importantly, the project is more than just the 3D content. By using geospatial and archaeological data that describes the site within its landscape, its context is included, providing a legacy that contributes to local historical environment records. Archaeologists can document weathering and erosion, changes in land-use, and gradual or sudden destruction over time, helping to inform long-term management of such sites.

The work has taken place at high-profile sites, including the 14th-century basilica of St Benedict in Norcia, Italy, destroyed by an earthquake, and Palmyra in Syria, attacked by ISIS. Others include Cyrene in Libya, Amatrice in Italy, Bagan in Myanmar, Diocletian’s Palace in Croatia, and Fountains Abbey and Drummonds Mill in Yorkshire.

Virtual reconstruction of the Temple of Bel, Palmyra

The Fossil Finder project provides a public web portal, inviting people to search for human fossil remains. Working with archaeologists and palaeoenvironmentalists based at the Turkana Basin Institute in northern Kenya, the team used an octocopter drone to take high resolution photographs of the landscape. The project invited the public to help the team interpret these images.

With the aid of citizen scientists online, the images of the surface could be scoured for rocks and fragments of bone that were out of place, as key indicators of the ancient environment.

The project has over 8,000 registered contributors from across the world, and many more casual users, who found and labelled new fossil finds in over 120,000 images, creating a new understanding of fossil density in the Turkana Basin.

The University partnered with Mercy Corps, Southern Azraq Women Association and Jordan Heritage to create The BReaThe Project – Building Resilience Wellbeing and Cohesion in Displaced Societies Using Digital Heritage. Using virtual reality refugees and other mixed communities could access heritage that was no longer available. This helped to reconnect people and stimulated discussion between Syrian, Druze, Bedouin and Chechen people as well as other minority groups, leading to a sense of belonging, social cohesion and greater self-confidence.

Professor Andrew Wilson said: “The University of Bradford has established digital documentation as a mainstay for heritage research. We have created a virtual resource and a drive for the ethical use of human remains data in education, our work with the global museums sector has enhanced public engagement through 3D scanning and virtual display, and we have enhanced the lives of refugees and displaced societies through work with digital heritage and co-creation as a new and valuable toolkit for social cohesion and wellbeing.”

Professor Andrew Wilson