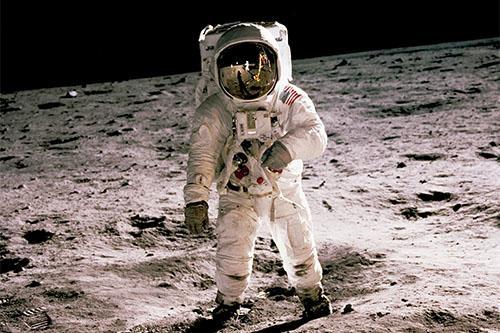

Could you tolerate your work colleagues on Mars?

A Bradford academic’s work on ‘trust in the workplace’ may bring success to a NASA Mars mission

For someone who is admittedly ‘fascinated by failure’, organizational psychologist Professor Ana Cristina Costa’s work is all about success. During her career, the University of Bradford academic has worked with numerous organisations, helping them foster environments which promote trust and transparency, attributes she says ultimately benefit the long term survival of a business. One of her more recent and high profile secondments saw her undertake work for US space agency NASA but, as she explains, the collaboration almost didn’t happen.

Professor Ana Cristina Costa

Her work, from 2016-18, saw her developing a study, Team Trust In Future Exploration Long Duration Space Missions, for the NASA Johnson Space Centre Mars Mission, which looked at the effects of prolonged isolation and confinement, essentially how astronauts might react when faced with spending 18 months away from Earth and an agonising 20-minute each way delay in communications while on the Red Planet.

Prof Costa was born in Lisbon. She initially wanted to become a clinical psychologist but says she quickly realised her true passion lay in the dynamics of trust in relationships and how they affect organisations, specialising in organisational psychology toward the end of her PhD degree.

After graduating in social and organisational psychology from Lisbon, she went on to work for several human resources management firms in recruitment and selection, training and professional development. In 1995, she entered academia, studying for a PhD in Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology at Tilburg University, Netherlands (1995-2000), before taking on her first postdoctoral role (2000-2002) at Delft University of Technology, assuming the role of assistant professor from 2002-2008. In May 2018, she moved to the UK to work as a senior lecturer and later reader at Brunel University, London. She joined the University of Bradford’s management school in the Faculty of Management, Law & Social Sciences in September 2018 as Professor of Organizational Behaviour and is also currently director of postgraduate studies.

She is also a visiting professor at the Research Institute of Personnel Psychology at Valencia University, Spain and a member of the European Association of Work and Organizational Psychology (EAWOP), the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP) and the Academy of Management (AoM) and maintains close links with the Chartered Institute for Personnel Development (CIPD), leading employers and alumni.

She says her research is driven by a desire to understand individual and team performance and wellbeing at work and adds:

“The central theme throughout my academic work is to understand organizational phenomena through the perspective of the individual.”

She has worked with government support organisations, community leaders, health care and other industry partners in both private and public sectors. In the Netherlands, she worked with multinational chemical company Basell “to enhance organisational learning through the introduction of management routines of reflexivity.”

To date, she has secured £500,000 of external funding through 14 grants. She’s also worked with other big names, including Xerox Europe, specifically on the negative effects of innovation and its consequences for employee performance. Her ongoing work with the British Academy/Levenhulme Trust is helping healthcare trusts rethink their promotion procedures from the perspective of the applicant, helping to make the process more transparent and ultimately more meaningful.

At Bradford, she led a strategic review which saw the entire restructuring of the postgraduate portfolio (10 master’s programmes). She is a member of the University’s Research Strategic Foresight Group led by the Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Research and Knowledge Transfer) to help shape the university’s research and innovation strategy and is a member of several editorial boards, having served as associate editor (2011-2018) for the European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. She is published in several top-tier journals including Journal of Management, Journal of Organizational Behavior, European Journal of Work of Organizational Psychology, Group and Organizational Management, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, among others. She has also edited and co-edited several books and handbooks.

“Trust affects performance at both the individual and group level. Much of my work has been about making the selection processes of companies more transparent and also about helping companies avoid litigation.” She cites a recent well-known case during which rejected candidates took to social media to voice concerns over the hiring process, creating a snowball effect and ultimately forcing the company in question to issue an apology and change its practises.

Prof Costa says the new digital economy has pros and cons for both candidates and companies. “Thanks to digital technology, companies now have access to a much larger pool of candidates but it’s also easier for people to apply for roles. But there are challenges in that. From the applicant’s perspective, it’s all about fairness. The more transparent the process, the fairer it seems. Even letting someone know they haven’t got the job is still part of the process.

“Using current technology, it will take 20 minutes for a message to travel from Earth to Mars. This means crews need to be much more autonomous and this is a problem for NASA.”

“The hiring of executives is arguably the most untransparent of all and the danger here is that companies end up hiring or promoting people who simply agree with their colleagues and while that might feel nice on a personal level, when companies do that, they often get what we call ‘groupthink’. They lose the ability to have critical thinking.”

It may have been this element of her work which led to her being approached by NASA. Its ambition to send people to Mars comes with all manner of problems, not least how to ensure the crew continues to function well once NASA is no longer able to maintain an instant dialogue with them.

“If the journey from here to Mars takes six months and they stay on the planet another six months and it’s six months to get back, that’s 18 months. Using current technology, it will take 20 minutes for a message to travel from Earth to Mars. This means crews need to be much more autonomous and this is a problem for NASA, because as an organisation, it is used to being able to monitor everything, from heart rates to blood pressure and then to inform crew members about that. With the Mars mission, it won’t be able to do that in a meaningful time.”

The solution, says Prof Costa, lies in the trust dynamics of the crew. She draws parallels with the performances of large organisations, including the NHS and multinationals. Ultimately, she says it’s about the avoidance of ‘groupthink’.

She says NASA took on one of her recommendations, which was to ‘invert’ the selection process: the new approach involved training candidates and then selecting them, rather than the other way around, which was the prevailing method. She says:

“For any mission to Mars to succeed, crews will need to be much more autonomous, to trust and rely on each other more than they previously did. The role of trust is very important.”

“If teams are becoming more autonomous and relying on each other, you have to have enough diversity not to create a groupthink effect, where everyone agrees with everyone else. This is how mistakes are made. You have to create an environment which nurtures critical thinking. If you’re continuously trusting, you lose the ability to think critically.

“For example, if you look at mistakes in aeroplane flights, when you track back, there has usually been some sort of decision based on an assumption that something was going to happen or that a device was going to work or that somebody had done something and in that moment, we find there was a lack of critical thinking.”

She is currently waiting to hear if her collaboration with NASA can be extended.

Commenting on her work to date, the Bradford academic, who cites painting and dancing among her hobbies, says: “Most academics are people who want to know how things work, they are curious. They try to identify a problem, learn more about it and hopefully contribute knowledge and help science move forward. I was always interested in how people related to each other and the organisations they work for. You can trust someone to do something. Or not do something but my work is about creating the best climate in which trust is beneficial.”