International peace symbol just as poignant today, says professor

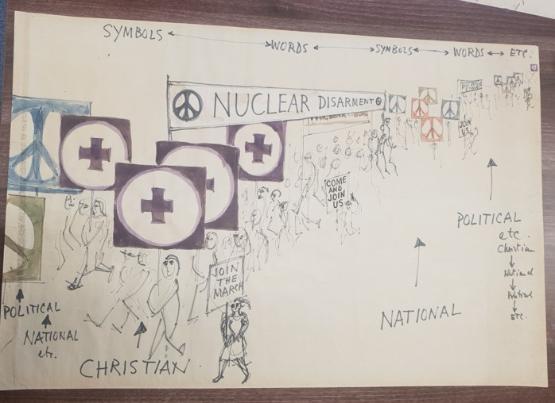

Hidden among the archives in the University of Bradford’s JB Priestley Library’s Special Collections, are the original doodlings of what later became the international peace symbol.

The sketches were done by Gerald Holtom in 1958 were designed for the Direct Action Committee to encapsulate the nuclear disarmament movement. The symbol ultimately went on to become associated with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

The original designs belong to the Commonweal Library but are cared for by the University of Bradford, which coincidentally is home to the world’s oldest peace studies department, which is presently marking its 50th anniversary.

Archivist Julie Parry with the sketches

As the world prepares to mark the second anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and with the ongoing conflict in Gaza, the symbol of peace, which is now recognised around the world, seems as poignant today as it did when more than half a century ago.

Holtom’s drawings show the evolution of the symbol, which in his own words was “representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad.”

The symbol also aptly represented the semaphore signals for the letters N and D (nuclear disarmament). He formalised the drawing and put a circle around it and at the time thought it “a puny thing”.

It was adopted by CND organisers but it wasn’t until a few days later, he realised: “if the symbol was inverted, it could be seen in a more positive way, as a tree of life” and a “symbol of hope and resurrection”, added to which its new orientation also represented the semaphore signal for ‘universal’.

A renowned historian of peace, Emeritus Professor Peter van den Dungen, who worked at the Department of Peace Studies and International Development (PSID) of the University of Bradford for over 30 years, said: “The pictures are the original drawings for the CND symbol – the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the UK. That symbol made its first public appearance [in Easter] 1958, from London to Aldermaston, home of the UK Atomic Weapons Establishment, where the British atomic bomb was made, protesting against nuclear weapons. The symbol has become world famous as the peace symbol.

“These original sketches, made by the artist Gerald Holtom, are the crown jewels of the Commonweal Peace Library in the JB Priestley Library.

He added: “The relevance of this particular symbol for the Russian war against Ukraine concerns the danger that the war could escalate into a nuclear war given the repeated warnings of the Russian president that he would use nuclear weapons if the need would arise to safeguard Russia’s claims in Ukraine.

“That the danger of nuclear war (whether deliberate, or accidental) is very real is shown by another potent symbol (even older than the CND one): the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. It stands at ninety seconds to midnight (Doomsday), the closest it has ever been.”

Statue rededication

As part of the Golden Jubilee events, he University’s Department of Peace Studies and International Development is due to hold a ceremony on March 7, from 3pm to 5pm, which will involve a rededication of the statue outside the JB Priestley Library, followed by a panel discussion on ‘reconciliation’.

The statue by Josefina de Vasconcellos depicts two exhausted figures, a male and a female, kneeling and embracing. It was originally called ‘Reunion’ and was meant to depict a woman being reunited with her husband after the Second World War, but was later renamed ‘Reconciliation' to recognise a number of significant world events and the individuals in the sculpture being metaphors for nations coming together.

Several bronze copies of this original statue were made between 1995 and 1998 and currently reside in the Bundestag in Berlin, Hiroshima, Coventry Cathedral and Stormont in Northern Ireland.

Professor PB Anand, Head of the Department, said: “The statue is significant for a number of reasons, not least of which is it represents the idea of reconciliation - at once so easy to think of and yet very difficult to achieve in practice.

"The statue was restored by two local artists, Lowri Morris and Jemima Latimer, last year after becoming weathered, so this ceremony is a rededication of the statue by our Vice-Chancellor. We have several speakers who will be discussing reconciliation from different backgrounds and contexts.”