A brief history of immersion, centuries before VR

Patrick Allen explores a brief history of immersion

milliganpuss, CC BY Patrick T. Allen, University of Bradford

milliganpuss, CC BY Patrick T. Allen, University of Bradford

Immersive experiences are fashionable at the moment, as virtual reality finally emerges into the mainstream with headsets now commercially available. But immersion is a technique much older than technology. It is the key to storytelling, in literature, film, videogames, even in the spoken stories told by our ancestors around the campfire. We are taken in by the experience: we become so involved with a character that we share their emotions, or build expectations about their progress in the story – and react when these expectations are either fulfilled or thwarted.

Look at immersion from a historical perspective and we see the rituals and social practices that gave rise to immersive experiences, and the relevance of the past to the hyped products of today.

In the middle ages, the use of stained glass in churches was designed to create an immersive sense of otherworldliness by bathing the church’s interior with coloured light. It was designed to provide churchgoers with a sense of direct contact with the divine, through visual stories aimed at a largely illiterate population.

Stained glass was an important form of visual storytelling. It was one of the ways that religious institutions could exert their hold on believers through the sanctity of messages delivered through colour and light, for which believers had to crane their necks up towards the sky to face the high windows.

A great example of this is the recently restored Great East Window at York Minster, a very large expanse of painted glass created in the early 1400s.

Great East Window, York Minster, which depicts scenes from the beginning and the end of the world. University of York

The sheer scale of this window is extraordinary. It is the largest expanse of glass in the minster and one of the biggest in Europe. All designed and created by one artist, John Thornton. Its subject is no less than the beginning and the end of the world representing in its huge number of panes scenes from Genesis and from the Day of Judgement. As such, it can be easily interpreted as a form of immersive storytelling for audiences of the late middle ages.

You can imagine the multi-sensory aspects of this experience: the design and shape of the space would have been critical to its impact on the audience, with light flooding in from the east. With dust and smoke in the interior, and the sound of a priest’s sermon and choir reverberating around the vaulted ceilings, even by today’s standards it would be pretty immersive.

Smoke and mirrors

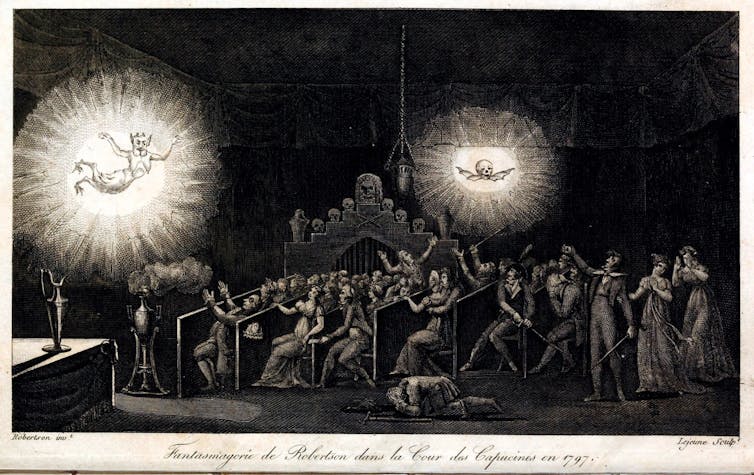

In the late 18th century, the quirkily named phantasmagoria used – quite literally – smoke and mirrors along with magic lanterns, a form of early image projector, invisible screens and sound effects to create a theatrical performance.

Recovered written accounts of the phantasmagoria are very interesting, as they link the rise in the use of magic lantern projections with the history of cinema. Via these immersive experiences, we get to the development of contemporary virtual reality devices.

The origins of phantasmagoria are associated with the work of German Johann Georg Schropfer who used magic lantern projections as part of monastic rituals – another form of immersive religious experience.

Participants would often fast for 24 hours prior to a performance and were greeted ceremoniously with drugged punch or salad. Skulls, candles and other monastic paraphernalia were used to set the scene. Accounts indicate that in these original performances three ghosts would be summoned, serving the monastic search for a deeper truth through contact with the spirit world.

Engraving depicting one of Robertson’s phantasmagorical shows and the effects they had on audiences. Memories by Etienne Gaspard Robertson

Inflicting terror

This soon became popular entertainment, and the showman Paul Philidor produced elaborate shows for audiences in Vienna. Another was the Belgian Etienne-Gaspard Robertson in the first few years of the 19th century in Paris. He would use three moving magic lanterns behind a transparent screen, accompanied by elaborate costumes and decorations and augmented with horrifying sounds, to inflict terror upon his audience. With the growing Victorian interest in all things gothic, phantasmagoria performances spread to England where they were delivered alongside seances to deceive, terrify and manipulate their audiences.

View Master slide viewer, developed in the 1930s and still available today. deiby, CC BY

View Master slide viewer, developed in the 1930s and still available today. deiby, CC BY

Some of the mechanics of today’s immersive experiences can be found in these early examples. The use of a projection system is common to phantasmagoria and to contemporary cinema.

Head-mounted displays seen in modern VR systems can be first seen in the stereoscopic imagery of the View Master, which dates back to the 1930s and is still available in children’s toy shops today.

An early 3D film showing at the Festival of Britain, 1951. The National Archives

An early 3D film showing at the Festival of Britain, 1951. The National Archives

From the 1950s, different cinematic techniques were introduced, including 3D cinema using stereoscopic glasses, an approach that still captivates audiences to this day – the 3D film Avatar is among the most financially successful movies of all time. I remember one of my first immersive experiences was watching How the West Was Won in the 1960s on a Cinerama screen – where a film is projected onto a giant, curved screen that provides an immersive experience via the wrap-around effect of the huge screen on the viewers’ field of view.

![]() So the current obsession with immersive virtual and augmented reality experiences will continue – we love our illusions and the stories that go with them. But we should not forget that to be swept away and out of the present by an immersive story is a timeless human desire, that’s origins go back as far as we do.

So the current obsession with immersive virtual and augmented reality experiences will continue – we love our illusions and the stories that go with them. But we should not forget that to be swept away and out of the present by an immersive story is a timeless human desire, that’s origins go back as far as we do.

Patrick T. Allen, Senior Lecturer in New Media Design, University of Bradford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.